The 2017 Public Sector for the Future Summit focused on how to make government better, faster, cheaper, and ultimately – citizen-driven by design. And in today’s political economy, strategies to achieve these new levels of innovation in government must not only deliver results quickly, but also with minimal impact on legislation, taxation, or regulation.

A vital new strategy for achieving this new level of innovation is the utilization of “nudges” in government operations and services. “Nudges,” per Nobel Prize-winning-economist Richard Thaler and Harvard Law School Professor Cass Sunstein, are “methods of augmenting the design of the environment in which people make decisions in order to improve individual and societal outcomes.” Nudges, per Thaler and Sunstein, shift behaviors that maintain freedom of choice, but have the potential to make people healthier, wealthier and happier.”

At the Summit, participants explored the growing use of nudges for improved societal outcomes, and in particular, the underlying levers of behavioral economics, analytics, and design thinking. While each of these levers provide tremendous opportunity for innovation in government in their own right, it’s the convergence of all three that has the power to dramatically reshape societal outcomes – and most importantly – create services that are citizen-driven by design.

Levers of Transformation: Behavioral Economics, Analytics, and Design-Thinking

To better understand how to not only adopt nudges in government, but also increase their ability to produce results, defining the underlying concepts of behavioral economics, analytics, and design thinking is our first step. We can define these concepts, or levers, generally as follows:

Behavioral Economics applies the consideration of psychological, social, and emotional factors, to the economic decisions of people and organizations. Traditional economics suggests that people and organizations will always make decisions that maximize beneficial outcomes, but reality shows that decisions are often heavily influenced by social norms, cognitive bias, framing of choices, the “ease” of decision-making, and simplifying (reducing complexity and increasing access) information. Understanding and rigorously using behavioral economics can help government not only better understand what programs and services may or may not work, or work better, but also help inform better overall design of the policies driving those services.

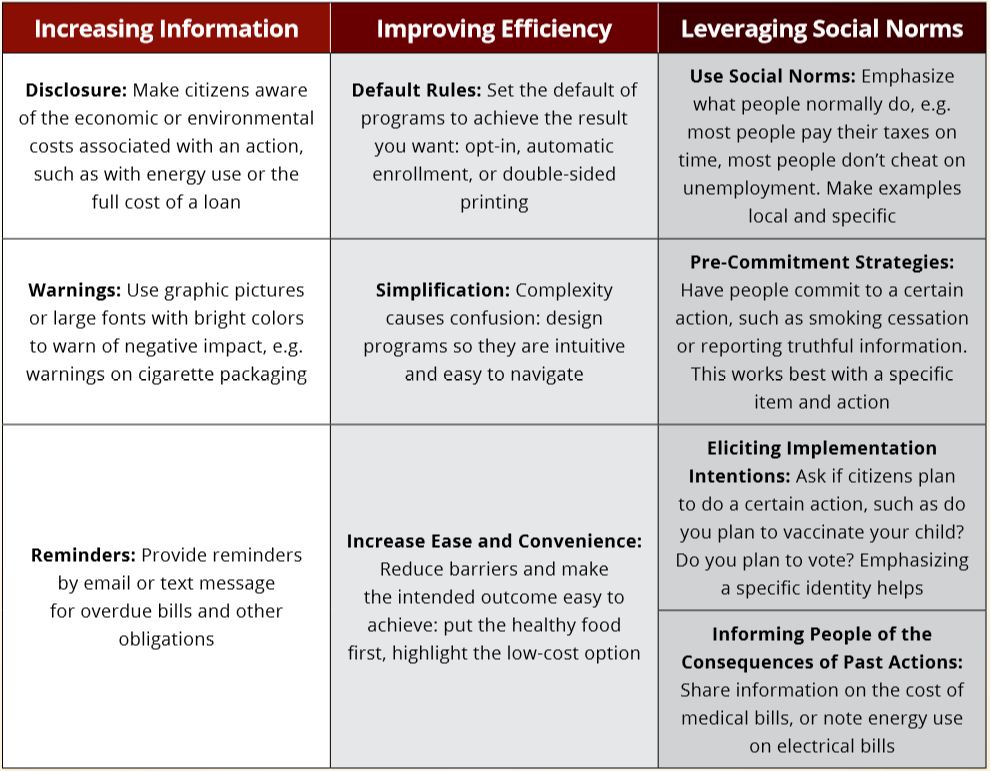

A key to applying behavioral economics in operations and services is a concept Thaler and Sunstein call “Choice Architecture” – the application of behavioral economics to the design of a decision-making environment. A decision-making environment is any product, service, or place where a customer is interacting to make a choice (whether consciously or subconsciously) and determining their next action. There are three broad strategies for employing choice architecture for nudges: Increasing Information, Improving Efficiency, and Leveraging Social Norms. (See Exhibit A adapted from “Nudging: A Very Short Guide.” ) Applying choice architecture helps alleviate some of the challenges to optimal decision-making for people (and collectively for organizations), as well as helps increase the potential for socially optimal outcomes.

For example, Pennsylvania used principles from choice architecture to develop an automated text messaging system that sends reminders for upcoming appointments, missed payments, and other events related to child support enforcement. Using texts, Pennsylvania’s Department of Human Services doubled the success rate of its previous phone messaging and increased monthly child support collections by more than $1 million per month. The texts provide more privacy than phone messages and improve the Department’s customer service.

Strategies for Emplying Choice Architecture For Nudges

Analytics are critical building blocks in designing and implementing “nudges”. Generally, data and analytics is the use of technological platforms, social networks, environmental sensors, inexpensive data storage, and data analysis methods that allow better measurement across the entire enterprise of inputs, outputs, and outcomes. Using analytics, public sector leaders can quickly assess the performance of a system from a wider perspective (e.g. across departments, agencies or jurisdictions), and even drill down to programs and operating units. This analysis can then drive innovation in the design and delivery of services.

Analytics also underpins evidence-based approaches to not only understanding outcomes, but also identifying nudge-type interventions that may improve outcomes. Evidence-based approaches use rigorous analysis of program investment, outputs, and impact relative to outcomes in order to quantify return-on-investment and other financial metrics. One application of evidence-based government is the randomized-control trial, which compares metrics of one program (via data on its outcomes and impact) to a control group or program. An important component of the scientific process, the use of randomized-control trials is rapidly gaining acceptance in social programs and initiatives that produce streams of data. This form of analysis provides an unequaled measure or “evidence” of a program’s results.

As a case in point, the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Food and Nutrition Service (USDA) used a randomized-control trial to test a simple, low-cost intervention using insights from behavioral economics and choice architecture. The USDA found that fruit placed in a colorful bowl in a convenient part of the school lunch line led to a 102 percent increase in fruit consumption. Based on these findings, officials can confidently scale up this type of choice-architecture intervention in school lunchrooms across the country. This is just one example where applying an understanding of human behavior enables the government to evaluate cost-effectively a program’s impact before committing resources towards a program or service.

Design Thinking is a human-centered approach to building solutions to complex challenges. As opposed to the traditional approach of developing government programs and services (which generally entails government agencies and contractors building a service that they think solves legislative mandates), design thinking uses a creative and iterative approach to put the broader customer (constituent/citizen) experience at the center of the development and delivery of programs and services. As defined by Leadership for a Networked World,“ Design-thinking is a solutions-focused approach to solving complex problems. Typically, it incorporates “tools” from designers, anthropologists, and others, and helps to reframe difficult problems, brainstorm solutions, develop prototypes, and quickly test ideas to achieve human-centered innovations.”

For example, Lutheran Social Services of Illinois (LSSI) realized that outcomes of their services could be improved if they could better integrate their network of programs, track a client’s journey as they accessed programs, and knit together a more tailored approach for select clients. To address this challenge, LSSI partnered with Accenture and Fjord to implement a design-thinking approach with real clients, which enabled them to better understand the interaction point between clients and services and how services could be better designed and aligned with outcomes.

Design thinking, when combined with behavioral economics and analytics, also enables more advanced methods such as behavioral design. By leveraging “evidence” from empirical insights and impact evaluation (such as fast-cycle randomized control trials), behavioral design helps assess program or service impact and iteratively builds those human-centered insights back into the design process, thereby improving the service design, impact, and outcomes over time. As a case in point, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs has used a version of behavioral design to improve access to services for veterans. The VA, in collaboration with veterans, developed a customer journey map to better understand and measure veterans’ interactions, decision points, and barriers and enablers to needed services. This behavioral design not only helped improve veterans’ services, but also guided the VA in its overall transformation.

The Nudge Loop: Five Steps to Improving Public Value and Outcomes

The convergence of behavioral economics, data and analytics, and design thinking enables leaders to create a “nudge loop” that helps inform the innovation needed to improve citizen-centric public value and outcomes. Start by picking a policy, program, or service and probing the following questions:

- Public Value and Outcomes: What drives public value? What is the policy, program, and service goal and objective? What types of outcomes are needed and how are they currently being measured? What is the variance between optimal outcomes and current outcomes?

- Behavioral Economics: What are the influencing factors and interaction points that frame and compel how decisions and choices are made by individuals and as organizations? Do current policies, programs, and services help or hinder people in making optimal choices?

- Choice Architecture: How can framing and the decision-making environment be improved to produce better choices and outcomes? What choice architecture can be applied where people or an organization interact with a service to improve decision-making?

- Design Thinking: From the perspective of the consumer, are current services built well? How can the design of front-office and back-office services, structures, systems, and processes be improved to enable better program and service delivery?

- Outcome Measures: What new outcomes are being generated? What data and analytics can be leveraged to assess program and service design and the effect of nudges? How do those measures and metrics inform the next version of policy, public value, and outcome goals?

Summary

The convergence of behavioral economics, analytics, and design thinking is a catalyst for making government better, faster, and cheaper. This new formula for innovation not only enables, but also accelerates, the power of Nudges in public sector programs and services. Going forward, the implication is that if policy makers and government executives can leverage principles from behavioral economics, analytics, and design thinking continuously into the design and delivery of government programs, constituents will be able to interact with government better, improving their decision making, and society will achieve more socially optimal outcomes.